When you either start a company or invest in one, there are a handful of ways to make money out of the whole thing. Generally speaking, the most likely way for both of those two groups to do so together is when someone else buys the company (or at least a large chunk of it). Now, while there is a certain amount written about the selling of companies, in my opinion it is nowhere near enough.

No matter how certain an opportunity looks, building (and for this you can also reading ‘investing into’) will always be a probabilistic exercise. I once had the agony of calling a founder, who had been waiting beside a pool with champagne, to tell him that a deal had died because what should have been a mundane customer reference call had gone inexplicably (and explosively) sideways. The signature blocks were ready and the press release had been drafted. Until an SPA is signed and the funds are wired to everyone’s account, you just don’t know.

I’m forcing you through this lens of uncertainty to talk about the context of early exits. Also, while I’m at it, what do I really mean by early exit? In the general context of business space-time, I suppose you could say it’s selling a company before you and your co-founders (and more frequently, your investors) believe it’s reached its ultimate expression of potential. Sometimes that’s described as a number, sometimes it’s just a feeling. For investors, it’s a valuation or IRR. Let’s be super-technical and call it earlyish.

Earlyish exits are historically controversial in VC-land, mostly because they are (usually1) significantly lower than everyone promised their LPs. That attitude has mollified in the last couple of years as fund DPI (Distributions to Paid-In capital i.e. cash returns) have become more valued as a signal for investing competence than solely TVPI (Total Value to Paid In capital i.e. paper returns).

There is never a version of advice about exiting (at any stage) which is not drenched in survivorship bias. For example, my general view on growth company exits is that you can either be too early or too late. Historically I have made most of my returns from being a little too early and I do not regret that2. But one can argue that my mental model is overly simplistic and, if you’re being really mean, lacks ambition. That’s a fair criticism. There are a very small percentage of builders who have vastly more amounts of money than anyone because they don’t think that way. The successful outliers prove me entirely wrong, the average and median proves me right. Choose your own adventure.

Although this post is about (or at least started being about) earlyish exits, I think much of this can be used to evaluate an exit at any moment in time.

Anyone who hasn’t been through an exit conversation thinks it comes down to price. It does but it’s usually the least important of the important points. I have six considerations when thinking about an earlyish offer. Although discrete, they both overlap and interact with each other and have different weightings for founders and investors. I have attempted to write it as a set of discussion topics which you might want to have with your co-founders/investors/board rather than just ranting3.

1. Has your industry got good growth prospects?

Total Addressable Markets (TAM) are both over and under-rated. Small niches can be superb (they’re some of my favourites) but a sector fuelled by structural growth (platform shift, demographic change, other things) can deliver great returns to even average teams. Over time I’ve become much more demanding in truly trying to understand the dynamics of markets. In general, TAM is always over-stated and the Serviceable Available Market (SAM) is always misunderstood. Advertising is an excellent example of this. The normal business physics of the sector are warped by a literal principle/agent conflict (media agencies) which permeates everything. But enough sector growth can fuel a company through even this kind of messiness (look at the multiples being paid for at-scale creator agencies for examples).

Discussion question:

Can your industry growth support 20%-100%4 YOY company growth for the next 3-4yrs?

2. Can your sector fundamentally provide a good return on capital?

In general, capital efficiency is a thing which most startups (and investors) don’t think about but really should. I think it was Buffett who talked about management energy expenditure in sucky industries, suggesting they’d be better off trying to move sector rather than optimise for terrible unit economics. Food-delivery is an obvious case in point. Are the winners worth the capital invested?

This point is often obfuscated by the fact that VC investments are, on average, mis-priced relative to the public markets5. An over-emphasis on growth over operating margin potential can lead to a lot of nasty shocks at later stage. I bang on about this point a lot but <loud voice> when you talk about revenue multiples, it is only shorthand for an assumed set of operating margins, not an absolute rule in itself. Casual investor chat of ‘we’ll sell for five times revenues’ will often be scoffed at by public companies who will calmly explain that they can only value you on an EBITDA multiples basis.

Discussion question:

Who are the best companies in your sector and how much capital will it take to get to their level of unit economics?

How are the public company equivalents of your company valued?

3. Is it a fair price?

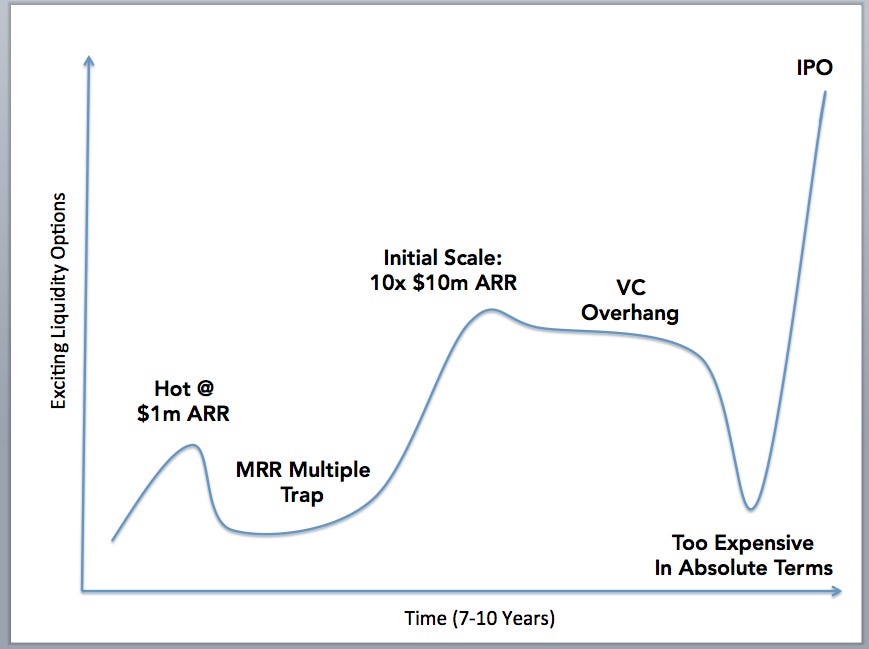

I often hear investors (especially VCs) casually say ‘oh we’ll just sell the company to X’ as if deals can be instantly summoned with some magical business incantation. Often (indeed mostly), acquisitions are functions of time/place/need rather than when people would just like them to appear: just because you have an offer on the table now does not mean you will be able to line up an offer in the future. Strategic exits in particular are a function of other people’s timelines, not yours (or your investors). Local maximum and local minimum pricing is a real thing.

It’s important to point out the flip side of this view (perhaps Claude Shannon’s Information Theory As Business interpretation) is that acquisition offers can be a signal that you’re doing the right thing and you should in fact continue..

Discussion questions:

The going okay-but-not-brilliant scenario: Does this pay shareholders (and founders) reasonably for the time which has been invested? Investors will have an IRR, founders should too.

The going-well-but-fragile scenario: With the right discount level (meaning cash today is worth more than cash in the future), does this pay you and your investors for some number of years into the future?

4. Is it a good structure?

There are some obvious and non-obvious things to say about deal structure. The obvious things are mostly related to price (covered above), consideration mix and what the acquiring company’s stock looks like. The non-obvious things to consider are:

I find a lot of people reject stock-driven deals without thinking about the opportunity it sometimes can be: shifting lanes into a sector with structurally higher valuation multiples which the company will simply never be able to unlock in its current vertical (this is especially true if the acquirer is public or has some degree of secondary liquidity).

There is a point in every deal scenario where founders become the tradable asset. Founders need to assess the deal in the context of whatever (probably inevitable) lock-in they’re going to have. This isn’t about time but also about quality of life in however the company is going to be integrated. I’m not saying this is a deal-breaker, I’m just saying think about it.

I love money, don’t get me wrong/but it’s more what the song’s like

For discussion:

How does the structure of the deal relate to everyone’s individual opportunity cost?

5. Where are you in the business cycle?

‘I think we’re in a bubble’ is an interesting point to make to investors, who are often rather hoping it isn’t. This is a near-impossible one to call but I’ve often found that just bringing up the topic focuses everyone’s thinking on the fact that a) bubbles do exist and b) whether gently or violently, they reduce in size at some point and c) in general if you’ve had a choice to sell within a bubble or outside of one, people (especially investors) prefer the former.

For discussion:

How would we know we’re in a bubble?

So, are we in a bubble?

What is the time-to-liquidity consequence of it bursting?

6. How long will it take to win?

This is an important topic, maybe for founders the most important topic. Founder energy is an incredibly important part of this factor. You may or may not want to have this conversation with your board, it really depends.

For discussion:

Have you got the energy for another five years at this (it may be less but this is a good psychological test)?

If you’ve finished reading this and feel that you’re just not sure about what to do, good. The point of this post was not to deliver you a decision, it’s to stimulate conversations which rationally analyse exit opportunities. I have a suspicion that at least some of you reading this (especially newer readers) were hoping for a post about how to exit early, in which case you’re probably doubly disappointed. I do have quite a few things to say about that but not today.

Notable exceptions include Instagram (2yrs), YouTube (2yrs) and several recent AI companies in these weird licensing/acquire things which I suspect investors hate.

It is still probably 30% rant.

This is an arbitrary range, for early stage companies I’d be expecting 100% YOY growth.

This is not (just) a VC thing. The FOMO nature of the startup/VC ecosystem creates all sorts of mostly obvious short term incentives for founders and investors which lead to pricing ruh-roh moments down the line.

Great post. I completely agree not enough has been written about this topic. I took can remember a large number of early offers that were rejected only for the company to fall at the next great filter.